about

“Music can open our hearts. That’s what I want the music to do. We all come from someplace powerful – we just need to find that place inside. My goal is to rest in that openness and let go. The more I practice this, the more my natural faith develops. The music finds its strength in that. That’s what I want to share.” FK

bio

“I’ve always been mostly interested in how music feels. I looked for the music that moved me the most and tried to understand how it worked. It never mattered where the music came from or who made it. My goal was always to feel both free and grounded at the same time. You have to feel it first and then find your own way to share that feeling when you play. Learning a musical language is a help to get that happening, but never an end in itself. It took me a long time to get to what I considered the bottom-line.” FK

read more...

Born in Montreal in 1956, Kiermyer’s family helped form the foundation for his interest in music. “My grandfather gave me my first drum when I was 8. He was a great Charleston, Foxtrot and Jitterbug dancer. My mother learned from him and she also became really good. The Saturday morning services in our local Synagogue are some of my earliest memories of the power of music. I always felt very warm in that environment. The singing would get very intense and passionate. There was a drone underlying the chanting that would really move me. Even though I was too young to understand much, I knew there was something special happening.

My father loved New Orleans and Swing music, especially Big Bands. I spent a lot of time listening to his records, from Fats Waller and Kid Ory to Count Basie and Duke Ellington. I loved that music. Sid Catlett. Baby Dodds, Minor Hall and Gene Krupa really impressed me. All of these drummers had a big beat. It felt loose, spontaneous and sure at the same time and I really responded to that. I’ve always gone for that feeling of power and release in my own playing.”

Mostly self-taught, Franklin did have sporadic classical percussion lessons from age twelve until age sixteen, although he never took lessons on the drumset. “I began studying snare drum with Paul Duplessis, a great percussionist and composer of contemporary chamber music. We focused on drawing the sound out of the instrument and always staying loose. Later on, playing tympani introduced me to the sensation of drum tuning and tone quality. I learned how to let the notes ring out and overlap. I tried to play my drum set with that kind of resonance. I’ve always heard the drums and cymbals as one instrument vibrating together, rather than a set of different instruments.”

His professional career started at supper clubs and private parties with his high school music teacher, Tony Kershaw, a British saxophone player with a great affinity for Stan Getz. The Hungaria social club, a frequent venue, presented great Romani trios that alternated with the standards and jazz tunes Kershaw’s trio played. Franklin was struck by the similarities between the Roma’s music and the sounds of his own roots. “I felt the same thing in a lot of the Bela Bartok music I was listening to. He cut to the roots of the folk music around him. The Roma players at the Hungaria had a spirit and urgency to their playing that felt familiar to me. It felt like a ritual and a celebration at the same time, like the music in synagogue.” By his mid-teens, Franklin’s spiritual yearnings found more focus. “I never really gave up on those questions about life I had as a boy. I thought that all the world’s spiritual traditions had freedom and peace as their goal, but I knew that this couldn’t be reached through philosophical studies – that it would have to be experienced somehow.” read more...

Montreal of the 60’s and 70’s was an important part of the East-Coast Jazz scene. Just a fast six hour drive, or one hour flight from New York City, all of the great bands would make it part of their touring itineraries. Growing up seeing legends like Dexter Gordon, Charles Mingus, Philly Joe Jones, Count Basie, Art Blakey, Duke Ellington, Elvin Jones and many others was an invaluable part of Franklin’s education. After leaving college at eighteen, Kiermyer started to take road trips with U.S.-based R&B bands – musicians he had met when they played Montreal. The next couple of years were spent at different local dives up and down the East Coast.

“It was good to be playing with good musicians and traveling, but I was dissatisfied because the music wasn’t right for me. I felt I could develop more quickly if I could focus my energy more on what I was hearing. I came off the road to live in Montreal again and sort of locked my self away to practice and study. I worked hard at it and after about six months I reached what I thought was a significant milestone.” On July 21st, his 21st birthday, a fire burned him out of the loft where he was living, destroying all of his belongings, including his drums and all the music he had written up to that time. “I was sharing the loft with a good friend, a guitar player I had known for a couple of years. He had a couple of close friends that were attending Hampshire college in Amherst, Massachusetts and they invited us to crash there for a while. They told us that we’d be able to play on the instruments in the music studio there, as no one was using them much. We really had nothing after the fire. Both of us lost all our instruments and belongings. My girl friend at the time worked at a clothing store and gave us each a change of clothes and we took the Greyhound for Amherst. The school was pretty relaxed and no one seemed to mind much that we were there, even though we weren’t registered as students. There was a new jazz program just starting up at Hampshire then, led by the bass player Vishnu Wood. Vishnu was very cool. He let me practice as much as I wanted in one of the music rooms. Not long after we met, he asked me to go to New York City and buy the school an old set of Gretsch drums and some good cymbals. I managed to find a great old kit and that’s what I ended up playing on every day. read more...

Soon, Franklin was organizing his own projects with the best players he could. Sometimes encouraged, sometimes humbled, he kept on trying to set up occasions and rise to them. As his vision grew, so did his reach. This became his method of moving ahead – practicing drums and composing to deepen and clarify his vision and improvising with the best musicians he could, to develop his playing. “I was trying to get my music out there so I tried a lot of different things. At one point, I recorded an album’s worth of my music with saxophonist Carter Jefferson, bassist Juini Booth and my old friend Fred Henke on piano. The next year, I put together a few nights at Grand Café with saxophonist Jerry Bergonzi and guitarist Mick Goodrick. The next year, I recorded duets with percussionist Don Alias and then, a few months after that, duets with guitarist John Abercrombie. I intended both the quartet and the duo recordings for release, but I wasn’t satisfied with my playing.”

When a young musician’s wings grow beyond local territory, New York has always the place to go. Kiermyer had been spending time there, visiting relatives, since he was a kid. In his early twenties, he started taking trips there to get closer to the music. At age twenty-six, he moved there. “Living in New York was very exciting. So much creative energy and will is focused in that relatively small space and it was great to be able to go around to venues and hear so many excellent musicians. It was also hard making enough money to pay for a place to live and food to eat. For the first few months I was living at a recording studio on 48th street near 9th avenue owned by some friends of mine. It was a great studio with a lot of activity, but not a great place to live peacefully, so I found an inexpensive room in an old building near Wall Street. I spent a lot of my time doing odd jobs for some money and the rest of my time practicing, playing with the musicians I was meeting and making the few gigs that came around. Still, I felt I was starting to find my way. I remember how excited I was to get the call to join Cuban percussionist Daniel Ponce’s band at the Kool Jazz Festival. Of course I assumed I was being hired to play drums, but my excitement was somewhat tempered when I understood that Daniel wanted me to improvise on a DMX drum machine with him and his three bata players. This was the ‘80s, the time of Grandmaster Flash, Run-D.M.C, The Beastie Boys, and Public Enemy – all of whom came through my friends’ studio.”

“During the 1980s, the jazz community shrank dramatically.” – Wikipedia

“It wasn’t so easy to find gigs. It was still good being in New York, but also a scuffle and after about a year of that I decided I should find a place where I could spend less time scuffling and more time developing. I needed to reach another level in my playing. I moved to Toronto, set up a practice-living space and got down to more focused development again. A good friend of mine in Montreal, a great guitar player named John Farley, told me about Michael Stuart, a Toronto-based saxophone player who had played in Elvin’s band. I looked Mike up and we quickly formed a close connection. He’d come around my loft almost every day and we’d shed together. It was a very good period of development for me. I stayed in Toronto for about a year and reached another level where I could start to do some of what I intended. I had started playing much broader phrases across the bar line. I tried to bring it down to a single event – one phrase in answer to all the rest that would stretch the time and cause it to open. I tried to expand the energy as much as possible while staying focused on the simple song or mantra in the center.” Following an intense breakup with his girlfriend, who had come with him from New York, Franklin moved back to Montreal. read more...

“Sitting in a coffee shop in 1987, I heard Franklin’s music for the first time. The impact was immediate: the swirling rhythmic interplay, the circular momentum, strong intervals that seemed often to spill upon each other, always driving forward, extending up and beyond. Sitting with this young man I had never met before, I was returned to musical images that have never left me, since long ago when I first heard Afro Blue, hearing Elvin Jones push McCoy Tyner and Trane into that kind of spiral that was travelling somewhere I desperately wanted to follow. I agreed to get the brass section together … all of us felt a strength and focus that we wanted to be part of. Franklin’s vision, in both his playing and his writing, is one of an extended search – I believe this reflects to a large extent the influences that one can readily hear. Who could ever listen to the young John Coltrane, and not feel a yearning, a seeking spirit that transcends categories of whatever people want to call that music. It’s difficult to open up this way – every normal instinct tells us to find a safe harbor. There is in Franklin’s conception an innate refusal to accept this.” - CHRIS GEKKER

Kiermyer moved back to New York City full-time and began a residency that lasted close to 20 years. This was the tail end of the 80′s, the height of what some people called the neo-conservative movement in jazz. It could have been distracting – Franklin’s music was focused more on creation than re-creation – but by then he was strong in his convictions. “It was still a scuffle to pay the bills, but I had a mission. I tried to get gigs at the many small venues in and around the city. I started recording some of the Jericho music.” ‘Break Down The Walls’, Kiermyer’s first album, released on the German Konnex label, met with some critical acclaim.

“Never has an album been so aptly titled. The music of Franklin Kiermyer, a drummer with an Elvin Jones-like intensity on his drum kit … is like the music of classical composers Bruckner and Mahler, one of searching and extending the search. That he imbues the search with such a range of physical motion and psychological emotion is remarkable … This isn’t free jazz, nor is it out jazz. This is methodically realized composition in the modal jazz idiom that reveals its unquenchable desire in every bar. (Think of Coltrane’s Africa Brass sessions with the spiritual and emotional underpinnings of A Love Supreme and you can glimpse it.)” – ALL MUSIC GUIDE

“Even though some people seemed to like Break Down The Walls, I wasn’t so happy with my playing on it and I felt that I hadn’t really reached my goals with this format. A lot of the music was composed and I couldn’t get a strong and spontaneous feel. I knew I needed to play looser and with more conviction, find a better format and learn more about leading a band.” His next record, ‘In The House of My Fathers’, with Dave Douglas on trumpet, John Stubblefield on saxophone, John Esposito on piano and Anthony Cox or Drew Gress on bass, was released by Konnex in 1993. This album focused more on improvisation and less on writing. Like Franklin’s first album, it was received well. Although he was encouraged by this marked step forward, he knew there was a lot of room for improvement. “I was still holding back, trying to direct things from the drums. There was too much conception and not enough freedom. I was still listening instead of hearing. Some people had been telling me about a piano player up in Woodstock that could really contribute to what I was trying to do. John Esposito and I formed a strong connection right away and we spent a lot of time together in the shed. John had come up playing with Arthur Rhames, so he was used to intense practice sessions. Working with John, I eventually reached a point where I felt my playing was doing more of what it was supposed to do. Along with more trajectory and freedom, the drumming had taken on a lot of size. read more...

The church of Coltrane has a street-sharp new priest: Franklin Kiermyer, a charismatic, 38-year-old drummer who is bringing the late saxophone god’s style of eruptive jazz rapture into the realm of pure rhythm. Saxist Pharoah Sanders, an original ‘Trane disciple, contributes elder cred-not that it’s necessary here. Kiermyer plays (and composes) with an almost evangelical belief in jazz as a form of pure inspiration. - ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY

“With Solomon’s Daughter, I felt I could finally do some of what I intended. It had taken me a long time to get to that stage. It had always been difficult to find people that could play with a high enough level of energy, conviction and faith so that I could really open up. Pharoah could do that – perhaps one of only a few people who could. Even though the structures of my drumming were still somewhat vague and I wasn’t able to control the energies, I felt that I had reached a milestone. Pharoah was very happy with what we had accomplished and that was gratifying. We made plans to perform together. Our first date was a release concert in New York City. For some reason, he pulled out at the last minute. I’m still not sure why. I didn’t know who to call to fill in. At that time, Joe Lovano had just come to great prominence. It turned out he was a fan of Solomon’s Daughter. He graciously agreed to join me and it went very well.”

Franklin Kiermyer Quintet featuring Joe Lovano – Sweet Basil, NYC: “Kiermyer supercharges spiritual modality … I predict it won’t be long before he’s a headliner.” – DOWN BEAT

Following Solomon’s Daughter, momentum gathered quickly and Franklin began to receive offers to perform as a leader at leading venues and festivals. “I needed to get out there and perform, so I put together a quartet with Michael Stuart on saxophone, John Esposito on piano and Dom Richards on bass, hoping that we’d be able to advance the music together. We worked hard on a new repertoire, trying to open up the energy and sharpen the focus. Taking this next step wasn’t easy. The music needed a high level of energy and faith and I saw after a while that it was a real challenge to get it there. We were playing gigs around and certain things were progressing, but overall it was frustrating. This was showing in my attitude. I was often irritable and discouraged because I knew that what I was putting out there wasn’t right. During this period I was listening to a lot of traditional spiritual music of different cultures. That was my study. I was also getting together to play with many different people in a rehearsal setting, looking for some alternatives, but nothing really seemed to fit any better. I didn’t give up on the quartet. I hoped that it would grow over time. Eventually, the label wanted another record and so I began working on Kairos.” The repertoire for Kairos (1995, Evidence) grew out of Kiermyer’s study focus. Pieces that intertwine his drumming with historic field recordings of various traditional ritual music alternate with simple themes improvised on by the quartet. Two of the cuts include saxophonist Eric Person and there’s also one sextet cut that includes Sam Rivers. The momentum that had been triggered by the release of Solomon’s Daughter was further fueled by Kairos’ reception.

“Most happenings are beyond expression; they exist where a word has never intruded,” Rilke said – recalling this year’s favorite inexplicables: Franklin Kiermyer Kairos the drummer pulses and pushes his group into middle Impulse!-era Coltraneland. What a journey, what a view.” – WASHINGTON CITY PAPER

“We were playing around more and more and after about a year I felt I should try to take the next step, with even less writing – relying more on the spontaneity. I thought that might help open things up more and let the natural energy come out.” Kiermyer’s growing interest in the techniques of recording his music led him to purchase a used 8-track digital recorder, some microphones and other gear. He started recording rehearsals. “I wanted to learn how to record what we were doing, as we were doing it. That way, we’d be playing in a natural, relaxed way – no studio time pressures, no headphones, no isolation booths – and capturing the spontaneity more. I was expecting the music to grow into a very free but deep-rooted heart-song, but it wasn’t really working like that. I was hearing something different, but I wasn’t able to communicate that, or the others were just hearing some other things. We just weren’t reaching the levels of energy and faith the music needed.” read more...

“Absolutely amazing stuff!” – Michael Cuscuna – MOSAIC, BLUE NOTE, IMPULSE, VERVE

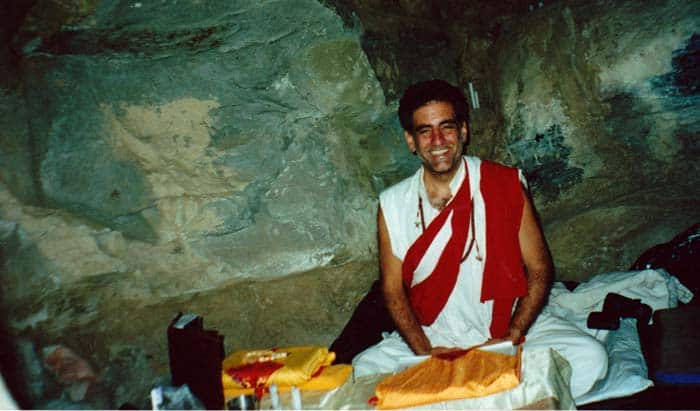

“During this time, I was very fortunate to meet a great Tibetan Buddhist teacher. In him, I saw the depth and openness I knew was at the source of great music. I would ask him for his instructions on how to practice. He’d tell me what to do and I’d go and do my best to fulfill that. When I completed a set of instructions, I’d go back to him and ask him again how to proceed. This went on for a few years and the instructions became more and more direct and challenging. As my experience slowly grew, I became happier and more flexible. Following his instructions like this, I spent most of the next twelve years focused mainly on meditation and practice, often in remote solitary retreats in the Himalayas and other parts of Southeast Asia." Halfway through this period, Franklin returned to New York briefly and recorded Sanctification (1999, Sunship) with Michael Stuart, John Esposito and Fima Ephron on bass.

“His quest is grounded in spiritual music … In the tradition of the ecstatic expressions of post-Coltrane acolytes such as Pharoah Sanders-a previous Kiermyer collaborator-Sanctification establishes a roiling atmosphere of a journey to enlightenment.” – JAZZTIMES

“I was becoming freer in my conception by then. I had these very simple themes for us to play on and I meant it as a kind of invocation. I was feeling that things were changing. The part of my life where I was chasing was ending and the part where I was finding was beginning. As my meditation practice slowly deepened, I became more confident in that feeling of openness. At one point, my teacher suggested I stop playing drums. He said, ‘Many people know how to play drums, but those that know that drumming is impermanent and empty of self-nature are miraculous.’ I had never been challenged like this before. I thought I was leaving drums behind forever. This was one of the most difficult things I’ve ever done, but it was worth it. When I eventually got back to playing after about six months, I had taken a big step in my looseness, openness and faith in the moment. I was studying the Uttaratantra Shastra at the time, which is translated into English as the Treatise on the Sublime Continuum. Known as the Gyu Lama in Tibetan, this text is a commentary on the Buddha’s teachings describing primordial nature. I think many musicians feel that music comes from that primordial nature we all share. My teacher asked me to make music using the twelve verses that refer to the metaphor of a drum.”

‘One who has arrived at the True Nature is like Indra, a drum, clouds, and Brahma – and like the sun, a precious jewel – and an echo, space, and also the earth.’ – Maitreya’s GYU LAMA

Great Drum of the Secret Mirror (2002, Sunship) has each of the twelve ‘drum’ verses of the Gyu Lama set in a different traditional spiritual music. Ranging from a South Indian Carnatic inspired temple dance to an African inspired balafon and drum ensemble, this album features only a little of Kiermyer’s drumming – notably the last piece entitled ‘Aspiration to Fulfill the Guru’s Instructions’. The vision of a global ecstatic music orchestra made up of master musicians from various spiritual traditions inspired him during this creation. This inspiration was the impetus for him to form Great Drum Foundation, a non-profit corporation dedicated to realizing that vision. “I created Great Drum Foundation to help integrate my activities. I wanted the music and my spiritual practice to be more closely related to what I was producing and sharing.” Over the next few years, GDF was the focus of Franklin’s work. Activities ranged from weekly Sunday afternoon concerts called ‘Sound Revelation – NYC’ that featured different musicians from New York City’s many spiritual communities to performances featuring master musicians from other countries, entitled ‘Masters of Spirit’. read more...

My girlfriend at the time was Norwegian. We had originally met in Kathmandu many years before and she would spend time with me whenever she could, wherever I was. Not long after I moved to BC, she came to visit.” It was during that visit that they conceived their daughter. The mother was adamant about living in Norway, so he moved to Oslo in June of 2006. They separated soon after Hanna was born, but Franklin decided to live in Norway to be there for his daughter. In 2008 he met his wife. Their daughter, Ava was born the next year. “I’m certainly happy that I did focus more and more on my spiritual practice and I’m happy I decided to be there with my family. I really feel these have done more to deepen my music than anything else I’ve ever done. Being together with my wife and daughters, and ensuring my girls grow up as sisters, has allowed me to go a bit more beyond myself. That's what I want the music to feel like. I had been focused more on meditation and my daughters, but my goals and motivation never left. It felt like the right time to focus more on music again, but this time more from the basis of what I had experienced in my spiritual practice. I put together a good workspace with some recording equipment and began inviting some local players to woodshed with me. After some time, I began to take it out to the local venues.” Pretty soon, it was time to assemble a strong band to take the next step. The opportunity arose to bring Azar Lawrence, Benito Gonzalez and his old friend, Juini Booth together to perform and then record some of his new music. Franklin then sent some rough mixes to Michael Cuscuna who was moved to sign on as co-producer to help guide the album to fruition. The fruit of this collaboration is Further, his 2014 album released on his Mobility Music label. read more...

“Franklin Kiermyer conveys a spiritual feeling through his music that reaches each listener in different ways. He has a way of expressing his work without being locked into a musical category. What’s unique about Franklin’s music is that as different as various settings are, it always sounds like it is him. The language created by John Coltrane with works like Sun Ship and First Meditations and by Pharoah Sanders with albums like Karma opened an avenue that proved popular and innovative in the late ’60s and early ’70s, but few chose to expand upon that language until Franklin settled in New York City in the 1990s and recorded Solomon’s Daughter with Mr. Sanders on tenor sax. Franklin has steadily built upon that foundation and this latest chapter in his musical step is a breakthrough. With this project, he is building a body of work that is wide-ranging with a singularity of purpose and an ensemble with which he can tour.” Michael Cuscuna

"After Further, I felt very motivated. I wanted to take the next step, but needed a fresh canvas - somehow less referential and more reverential. I started spending more time in New York, checking out a lot of younger players and trying some different things. I was fortunate to assemble a strong group willing to develop this with me."

Closer to The Sun, released in 2016, was again co-produced with Michael Cuscuna. It documents the period from October to November, 2015. During a five-week period, saxophonist Lawrence Clark, pianist Davis Whitfield, bassist Otto Gardner and Franklin came together each weekday to record for three hours. Most of the songs were created on the spot by Franklin and the group.

"I came in with new themes and songs and we played through a lot of it, but I saw that we'd be better served to focus on the interaction and let that evolve the pieces organically. I'd sing a melody or play an idea on the piano or the drums and the band would develop on those themes. Sometimes, I'd take something one of the others played and used my reactions to that as a starting point.

The development of Closer To The Sun really hit home that what we're aiming for can only be reached by providing the time and space to work in such a focused way with a group of soulful, brave, passionate and sensitive musicians. It's really the only way this music can achieve what it's supposed to do. It hasn't been easy to find the right musicians. Besides the high level of skill and experience on their instrument and depth of sprit, one needs to commit to the process of developing as a group, which takes a lot of time and effort."

Davis and Otto were sure they wanted to proceed. Laurence Clark didn't feel it was the right time for him and so by late 2016 Franklin, Davis and Otto found themselves looking for a fourth musician. They searched high and low and got together with whomever they thought might fit. When they played with saxophonist Jovan Alexandre, they all felt the potential and decided to go on together.

The quartet set up a loft-studio in Greenpoint, Brooklyn to develop and record their music and began a rigorous schedule of daily sessions and shows in and around New York at venues including Small's, Minton's Playhouse, Smoke, Black Eyed Sally's, Zinc Bar and Rockwood Music Hall. Over the course of the next six months, the band recorded and mixed three full albums of material.

In late 2017, they decided to give the band its own name to differentiate this new music from what Franklin had done before. Davis suggested the name should somehow refer to Franklin's spiritual practice.

"The first thing that came to mind was a spontaneous song my teacher had sung to me many years before when he was instructing me to practice Chöd."

“Take this big corpse of the five skandhas and burn it in the realization of selflessness. Scatter the atoms that remain in the space of the Dharmadhatu and in the Dharmadhatu of no attachment ... Ah! Ah! Ha! Ha! Aaaah!” Khenchen Tsutrim Gyamtso Rinpoche

Thus the band was named "Scatter The Atoms That Remain".

In February of 2018, Scatter The Atoms had their debut at Jazz At Lincoln Center Dizzy's Club. It was a resounding success.

“"... a sense of shared catharsis through music that is at once majestic, ferocious, and relatable ... the words “ecstasy” and “ecstatic” appear almost predictably, but sometimes a word is just right. Scatter The Atoms That Remain channel the kind of beautiful, disciplined intensity exemplified by late John Coltrane. This type of universal, non-denominational spirituality simply feels good." Jazz At Lincoln Center

The next twelve months were half-filled with East Coast shows and intensive periods in the studio with the band. Franklin travelled to Nepal for a few weeks to see his teacher and give a workshop masterclass at the Kathmandu Jazz Conservatory. The rest of the time he spent back in Norway with his wife and children. In late 2018, plans were made and contracts signed with Dot Time Records for the 25th anniversary re-release of Solomon's Daughter and the debut Scatter The Atoms That Remain album "Exultation" scheduled for Spring 2019.

“Franklin Kiermyer has found the perfect vehicle for his spirit. Scatter The Atoms That Remain combines the emotional , spiritual and compositional forces that harkens back to Franklin’s epic release Solomon’s Daughter (recently reissued by Dot Time Records). Franklin has continued Coltrane’s legacy not as a tribute band but as a starting off point to help charter unknown worlds. This ensemble is a formidable Quartet. As you listen to this release you will feel the communication between the musicians and the respect they have for each other. As the band states on their website, The Soul – the heart – the qualities that set us free…this transformative power of music is what Scatter The Atoms That Remain is all about" Michael Cuscuna

In March 2019, Scatter moved in to a new studio in Hoboken, New Jersey, just a 15 minute swim across the Hudson river from Greenwich Village. Their first tour abroad took them to Austria, Germany and Belgium in April, during which, Exultation was released to widespread acclaim. Throughout the two-week tour, wherever the band went, the music was met with passionate response.

"Call it inspiration, intoxication or rapture. You feel it when it is there and the feeling was unmistakably present." Guy Peters - ENOLA, Belgium

Despite the success the band was enjoying, half-way through the tour, Jovan Alexandre began expressing his desire to retire from the band to lead a simpler life at home. He spoke of life-long issues and his feeling that he needed to scale-back to be able to take better care of himself. It was decided that Jovan would finish the tour and subsequently leave the band. Nonetheless, the rest of the shows were filled with joy and just as well received. Once again, Franklin, Davis and Otto found themselves in the quest for the right fourth member that would fulfill their promise. This time, the pressure to find someone was exacerbated by their contracted commitment to be in Germany on June 7 as the opening act at the 48th annual Moers Festival – certainly one of the most important performances they had as yet been offered. By now, the music Scatter was playing had grown to be uniquely their own, requiring a very high level of intuitive interaction. Relying little on pre-determined songs, each musician was charting his own trajectory, at the same time resting in the faith the collective improvisation was built on. With less than eight weeks to find a musician strong enough and brave enough to take on this challenge – someone that could grow with the band and stay the course – they found themselves at the mercy of fate. Then, a young saxophonist named Michael Troy identified himself as Jovan's replacement. It seemed like it could be a good fit. Announcing Jovan’s departure Franklin wrote: “Jovan Alexandre, one of the founding members of Scatter The Atoms That Remain, has decided to leave the band to follow his own pursuits. We could not have reached this far without him and wish him all the best going forward on his path."

"Scatter The Atoms That Remain provided the highlight. Pianist Whitfield dissolved his piano devils supported by bass player Gardner. Drummer and group leader Franklin Kiermyer conducted everything with masterful hand(s). Forget Kamasi Washington, THIS IS THE REAL THING!" Jazzenzo Magazine - Germany

A few months later, Franklin wrote: "Here we are now, mid-August 2019. I've just come from three weeks with my wife and children visiting our family in Montreal. This precious time together gives me so much that can't be described in words. I'm back in the band's Hoboken studio tomorrow to start working again. We'll be recording new music and playing more shows throughout the rest of the Summer and Fall – we'll be back at Lincoln Center Dizzy's Club on October 2 – and we're busy booking tours for 2020/2021. Over the years, I never gave up on my goals. I shifted my focus to working through what was holding the music back. If you listen, you’ll hear it’s further now. I’ve had a vision of what the music could do - what it could feel like, for a long time. I’ve developed a way of playing the drums and creating songs to make that haopen. It feels like all the things I’ve worked on, learnt and experienced have led to this period where it all comes together and I'm grateful for that.”

Updates coming soon:

• Michael Troy stayed with the band until early February 2020.

• Emilio Modeste - Emancipation Suite recorded 2 weeks before the pandemic really hit in late-March 2020 ... To be released Summer 2021

• Ben Solomon working with the band

• Video series: Duos & Trios on Tuesday and Solo Fridays

• Shows begin again September 2021

• Scatter tours Europe for the first time - January 2022

• Gerorge Garzone, Gene Perla, Abraham Burton play with the band

• Begin working with Jason Olaine

• West Coast USA + Europe tours - January 2023

• Lincoln Center with Randy Brecker and Billy Harper - May 2023

• Europe tour with Gary Bartz - May 2023

• Inaugural Unity Festival - Jazz At Lincoln Center - January 2024 with Randy Brecker and Billy Harper, Isaiah Collier and Nat Reeves.

• New Album in the works - One Is Love

writing

the spirit of drumming

drumming

this is what I think a drummer should practice ...

Start by singing a simple improvised motif or song fragment that is the most natural to you, like a chant or a prayer. Dig deeper until you hear the heart of it that moves you the most.

This is the beginning of finding your sound. Finding your internal song is the key and the quest. It should feel like a very familiar theme or song to you, not a drum pattern.

Always remember these 4 essential points:

1. Always stay loose and relaxed

2. Bring the sound out of the instrument, don't try to put it in

3. Each note should sing out fully

4. Hear – don't listen. Feel – don't think

Then. do these while singing your song:

• Play it on the snare drum – loose

• Then play it on the snare with bass drum & hi-hat

• Then play it using different parts of the kit

• Bring it down to its essential groove and repeat

• To get deeper into it, try stopping in different places

• Also starting in different places

• Then try it with more notes and less notes

• Finally, drill down to its core to develop clarity and fluidity

If you have any questions, just drop me a line on the contact page

questions

great doubt? then certainly great awakening!

read more...

close

drums

about my drums & cymbals...